Με το Windows Ink η Microsoft φέρνει σε όλους τους υπολογιστές, αλλά και τις ταμπλέτες με Windows 10, αυτό που ως τώρα ξέραμε όσοι ασχολούμαστε με δημιουργική ή παραγωγική εργασία σε υπολογιστή. Ότι μόνο με τεχνολογία Wacom γίνεται! Διαβάστε εδώ μια εξαιρετική ιστορική αναδρομή, από τα πρώτα βήματα της Apple στην δεκαετία του ’70, ως το multi touch που χρησιμοποιείτε στα κινητά σας τώρα που διαβάζετε αυτό το άρθρο.

The Company That Waited Decades for the Touchscreen Revolution

How the stylus-controlled graphics tablet, most notably produced by Japanese firm Wacom, helped shape our multitouch-friendly world—even if that shaping took a little while.

Image: Cyrotux/Wikimedia Commons

A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium, a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail.

These days, nearly everyone owns a touchscreen device of some kind, and odds are, you’re probably reading the opening lines of this story on one.

But there was a time, not that long ago, that touch-based devices were less common and often had more specialized uses. Around 2006, for example, before the release of the iPhone, my primary touch-based device had nothing to do with a phone. In fact, I couldn’t even interact with it using my finger; it required me to use a pen.

See, I worked in graphic design—mostly in newspapers—and as a result of that, I owned a tablet. For drawing, of course. It didn’t have a screen.

I wasn’t a great artist by any means, but that little Wacom drawing tablet was nice when I was tweaking cutouts and hopping into Photoshop or Illustrator. (I’m pretty good at cutouts if I do say so myself.)

Wacom was ahead of the curve on touch computing by multiple decades. (And it wasn’t even first!) And even if Wacom didn’t lead the touchscreen revolution, there’s a lineage between these computer drawing tablets and the touchscreens we eventually got. Here’s how one influenced the other.

“Only a little reflection will show that nearly all of the information used by business data processing computers originates in the minds of humans. What is needed are methods and devices which will allow these people to produce, by simple and inexpensive means, the initial expression of their information in a form suitable for machine reading.”

— T.L. Dimond, an engineer and executive at Bell Labs, describing the use case for handwritten character recognition in a 1957 article. “Without these,” he adds, “there will be many situations, especially where the volume of input information is large in comparison to the amount of processing, where computers cannot be proven even if they cost little or nothing.”

Dimond’s article introduces the concept of the Stylator, a device that is considered the first-ever computerized pen-based drawing tablet. The device was primitive, only accepting characters, but it worked in real time. It, along with the Rand Tablet from 1963, were the earliest forms of stylus-based input.

Before there was Wacom, there was … uh, Apple

The first tablet Apple ever released came to life because of weirdo rock icon Todd Rundgren, best known for the soft-rock staple “I Saw the Light.” No, really.

In 1979, Apple released an officially branded graphics tablet, which came to life on the Apple II thanks to Rundgren’s Utopia Graphics Tablet System software, which he ended up working on due to his affiliation with the New York Institute of Technology, a hotbed for computer graphics technology at the time.

“Essentially, this was the first example of a paint-box program that used cutting-edge programmers tools to build a tool intended for artists, not necessarily programmers,” Rundgren told The Guardian in 2004 of his software. “It was meant to be a companion program to graphics tablet hardware that Apple was going to put out as an accessory to the computer.”

Unlike some of its later creations, Apple didn’t actually create the tablet itself—it worked with a firm called called Summagraphics, which created an officially licensed graphics tablet for Apple that was released in 1979. At the time, Summagraphics had built a mini-empire from the Intelligent Digitizer and the Bitpad, both early drawing devices that were white-labeled and sold by other manufacturers—and likewise, the Apple Graphics Tablet was a rebranded Bitpad.

The Apple Graphics Tablet was truly novel for its time, especially before the Macintosh made computer mice common. But it had a knack for disrupting radio waves, which was a problem because many Apple IIs were connected to television sets during this era. It was a big enough problem that the language in a 1981 manualfor the Bitpad one noted the interference the device would cause. The FCC forced Apple to yank the device from release, killing its momentum.

Eventually, it saw re-release in 1983, at which point a smaller device called the KoalaPad hit the market not just for the Apple II, but for most of its competitors of the era. That device was well-regarded for its time, not incredibly expensive, and actually supported finger-based touch input, which prior tablets didn’t.

While the KoalaPad was sold for drawing purposes, it probably was more of a direct precursor to laptop touchpads—as YouTuber The 8-Bit Guy pointed out in a video last year, the Commodore 64 GUI GEOS actually supported it.

Wacom, despite eventually becoming the primary brand covering this niche, didn’t show up until several years after the tablet concept had already hit, but it soon came to define the entire sector.

How Wacom’s innovation game gave it the upper hand in an important market

Wacom’s early years in the market for drawing tablets really highlighted how quickly a single company could take over an entire niche with strong technology.

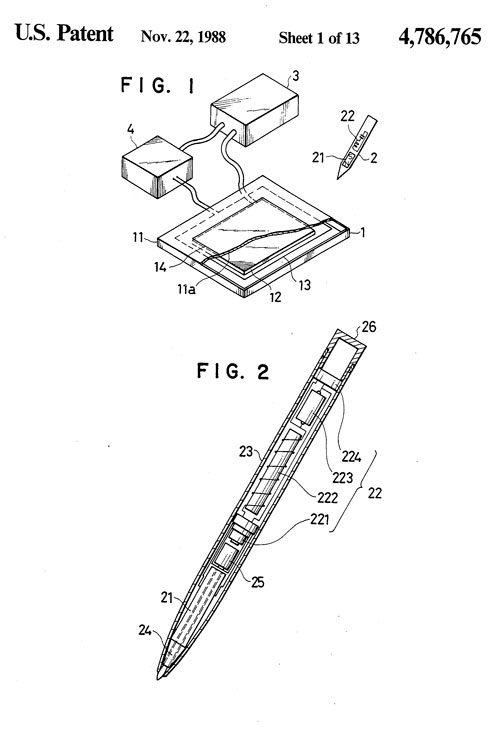

The company, founded in Japan in 1983, came out with its first tablet, the WT-460M, the next year. The firm made its initial name on offering tablets with cordless styluses, rather than the corded devices that competitors like Summagraphics were known for at the time. The firm launched during a period when many companies were getting involved in the space during the rise of computer-aided design (CAD), and its first offerings were focused on the drafting market.

A quick scan of the company’s patent filings on Google Patents tells an important story: Almost from the day of its initial launch, the company was aggressively inventing new types of technology to better detect and position how a digital pen interacted with information that was being displayed on a screen. It was clear that the company was intently focused on continually improving what a stylus could do.

Among the things that the company invented was a technology called electro-magnetic resonance, which allows its styluses to generate energy and interact with a tablet without actually needing batteries themselves.

In a 2006 interview with Japan Spotlight, a publication of the Japan Economic Foundation, current Wacom CEO Masahiko Yamada, who has served in his role since 1996, emphasized that the company ended up becoming the drawing tablet industry’s biggest player because it took a focused approach to the technology it was offering.

“Although our company was a late entrant and small in scale, we recognized the potential for the electronic pen and sensor board input system based on electromagnetic induction phenomena from an early date, and decided to concentrate our development efforts in hand-drawn CG production on the assumption that it would help people input data more freely,” he said in the interview. “We eventually came up with the concept of ‘graphic tablets.’”

Eventually, Wacom ended up selling the Walt Disney Company on the technology, which the company then used to produce the animated Beauty and the Beast, a major turning point for the use of computers in animation. (The company, starting with The Rescuers Down Under, introduced the use of the Computer Animation Production System for digital ink and paint, making Wacom tablets particularly useful.)

“The quality of this film was broadly recognized, and soon many film production companies and animation production companies in Hollywood started to adopt our product. Disney is still our largest user even today,” Yamada added in the 2006 interview.

Another thing that gave Wacom a leg up was a total fluke incident involving a key law at the start of the internet age.

In 1996, President Bill Clinton used a Wacom pen and tablet to sign the Telecommunications Act of 1996, marking the first time an electronic pen had been used by a sitting president to sign a bill. Notably, Clinton first signed the bill using the pen that Dwight Eisenhower used to sign the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956, which established the interstate highway system.

Yamada noted that the use of the digital pen, which was requested by the Clinton administration, “contributed greatly to our company’s fortunes.”

Wacom was ready for stylus-based computing to go mainstream before everyone else

Digital artists have long appreciated Wacom’s technology, which became more heavily used by regular consumers over the last 15 years or so with the release of the company’s Intuos and Bamboo tablets, which were often targeted at consumers.

(Earlier models, which cost a heckuva lot more—see the price list in this PC Magazinereview—were a little more out of reach.)

Of course, as much as it was great for digital artists, the real opportunity for Wacom was the possibility that someday, touch computing would go mainstream in a big way.

Let’s just say that the company was ready really early. While Wacom couldn’t say it was responsible for the first stylus-based tablet (GRiDPad, which appeared around 1989, was the first successful one), it played a role in one of the earliest attempts to bring pen computing to DOS and Windows, the NCR System 3125. The tablet appeared in 1991—complete with a Wacom pen. (Of note: The GRiDPad had a wired pen, while the System 3125 did not.)

The tablet, the low-end version of which cost $4,765 at the time of release (or $8,564 today, with inflation included), offered a pen-driven experience in DOS via a custom OS, Windows for Pen Computing, and multiple other operating systems.

It was the first of many machines to tackle the issue, and it was part of a larger race to win what was expected to be a major market, with companies like Apple taking stabs at the stylus game at the time.

“The expected boom in pen-based computers is setting off a furious race to develop a crucial yet often overlooked technology for these machines: the system by which the computer determines the position of the pen,” reporter Andrew Pollack wrote in The New York Times in 1991, in an article that prominently featured Wacom.

Wacom was particularly well-positioned to take advantage of the forthcoming pen-computing revolution in the early 90s, but there was a problem: The revolution didn’t come.

In fact, it took two decades to arrive, and when it did, the stylus was optional in many cases.

By 2006, at a point when Wacom had found a sizable niche in the consumer market, Yamada clearly spoke with optimism that the stylus still had room for a mainstream breakthrough.

“We will be thrilled if in the future the people of the world would feel the advent of the electronic pen was a good thing,” Yamada said in the 2006 Japan Spotlightinterview. “We are moving closer to that goal by trying to achieve harmony between technology and people’s sensitivities. After all, the ‘wa’ in Wacom means ‘harmony’ in Japanese.”

It’s pretty safe to say that, though it took a little while, Yamada got his wish.

Certainly, Wacom carries an interesting role in modern computing. It makes products that cover literally every corner of the tablet market—from low-end consumer products designed for sketching out ideas to high-end products designed for serious graphic artists. (Also, it sells standalone styluses, just in case you wanna use one for your iPad or something.)

Last year, in fact, the company launched a device called the Wacom MobileStudio Pro, which is basically a very high-end touch-screen Windows tablet for people who don’t find the Surface Pro to be enough of a beast.

In its most recent quarter, the company saw its sales jump by 20 percent year-over-year, with the company’s sales improvement being driven both by the MobileStudio Pro and a surge of interest in its styluses.

Of note, though, is that the company has become a major supplier of technology to other vendors, such as Samsung, which uses the technology in some of its smartphones. Wacom also works pretty closely with a lot of laptop-makers on the Windows and Chromebook side of things.

(Notably, Wacom wasn’t really involved in the iPad—a bummer, perhaps, since it was long associated with Mac-based computing—though it sells plenty of styluses that work for Apple devices.)

It took about 30 years, give or take, but all that work that Wacom put into improving the digital stylus is finally starting to pay off. Talk about playing the long game.